Hell Yeah or No

Author(s): Derek Sivers

How much I would recommend this book to other medical students/residents: 9/10

Buy it on Amazon: Link

This book outlines thinking principles that I have applied to my learning is a resident. A few other learning points I took away from this book are:

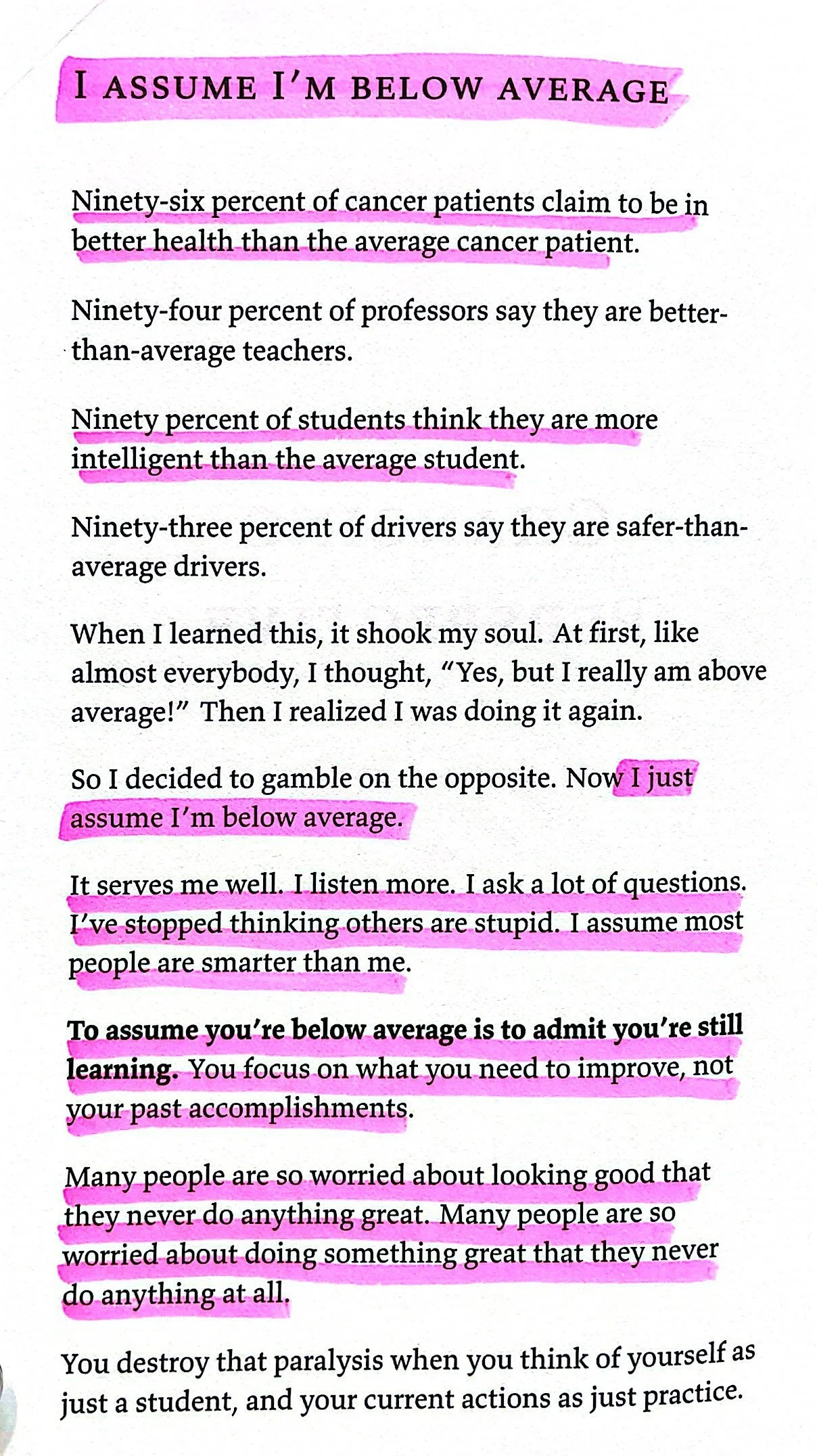

How assuming we are “below average” can help us learn more.

What sand dollars can teach us about working with medical students.

How periods of disconnection can help us improve our productivity.

How, in many situations, “I don’t know” might actually be the smartest answer.

Could assuming we are a “below-average” resident help us learn more?

As a medical student, I think there’s so much pressure to “look good” on rotation in order to get a good rotation grade.

It’s a bummer, because this directly inhibits students willingness to ask questions in fear that it might hurt their rotation grade.

Now is a resident working with medical students, I appreciate when students aren’t afraid to ask questions. In my opinion, the more that we can support student’s communicating what they don’t know (rather than strongly emphasizing always having the correct answer) the more students will learn on their 3rd and 4th year rotations.

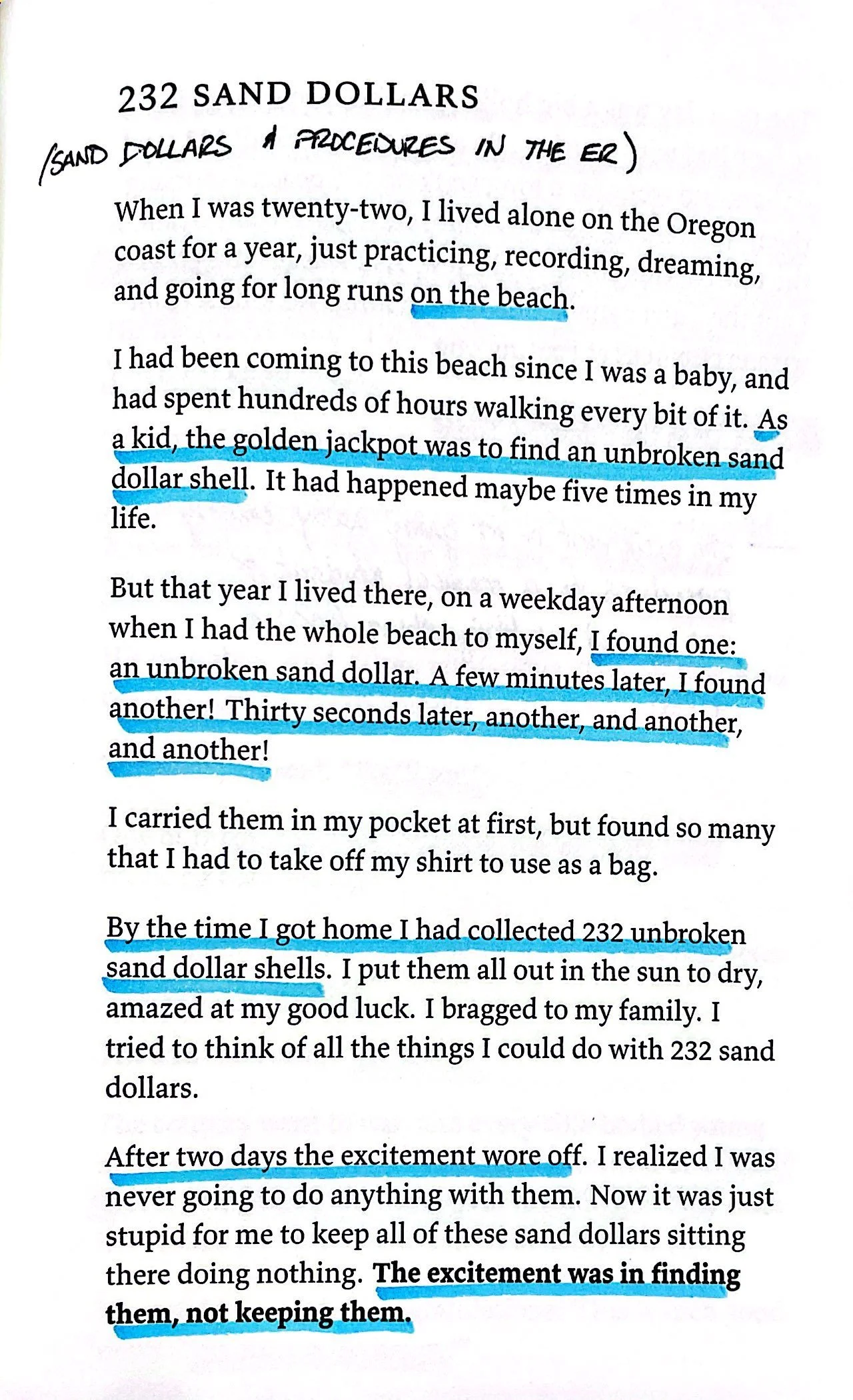

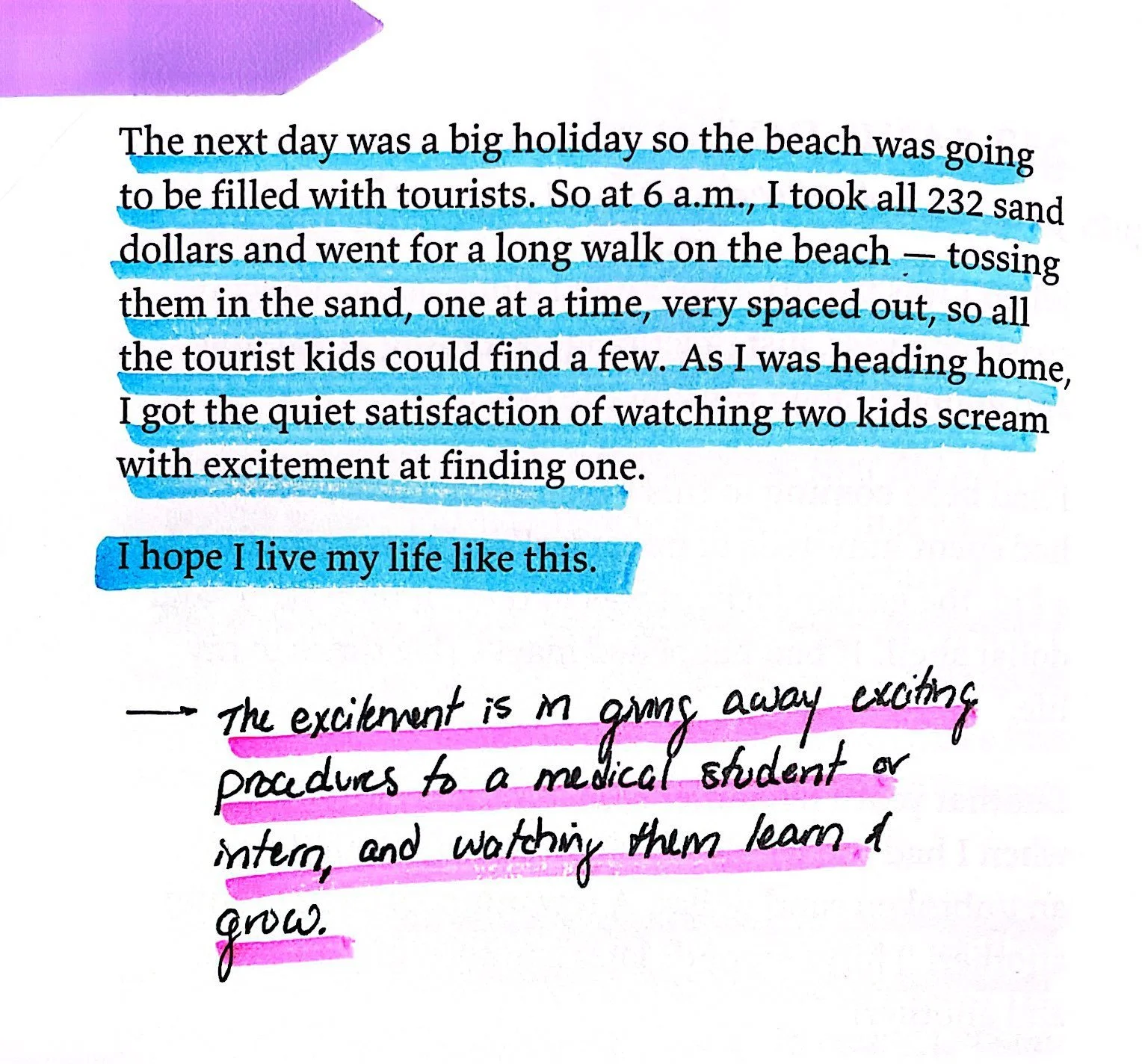

What can sand dollars teach us about working with medical students?

This reminds me of the process of working with medical students as a resident. There are many times that an interesting patient case might come through the front doors of the Emergency Department, or occasions when the opportunity for an interesting procedure might arise. From a teaching standpoint as an upper level resident, it’s way more exciting to let an underclassman learner assist and learn than to do everything myself.

Yes, there’s always excitement in performing procedures yourself. In my experience, it feels even better and is actually more exciting to give them to someone else where it will make a greater impact.

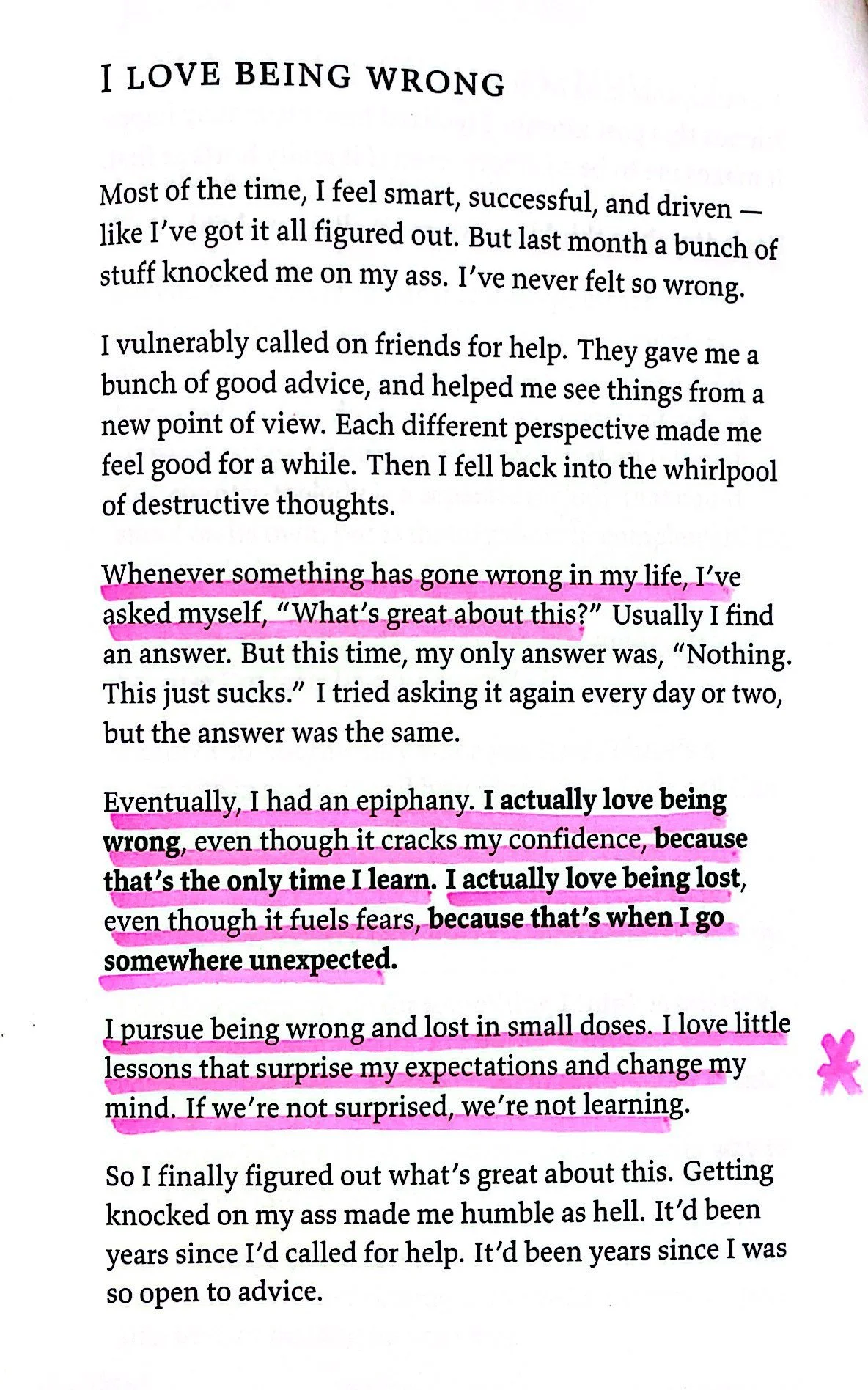

Why would someone love being wrong?

The learning curve in residency is a roller coaster of ups and downs. Just when I think I have something figured out, I’ll have a patient case that surprises me. That’s part of the excitement of it all. In many ways, it feels good to be wrong. Because when we’re wrong, we know that we’re learning.

How might reading about other disciplines help us improve our practice in Emergency Medicine?

This is essentially the focus of this “book highlights” section of this website. Just about everything that I read, I read it metaphorically and think about how my some of the concepts apply to our job as Emergency Medicine physicians.

Of course, not everything that I read applies to Emergency Medicine. But when I find something that might, it’s a lot of fun.

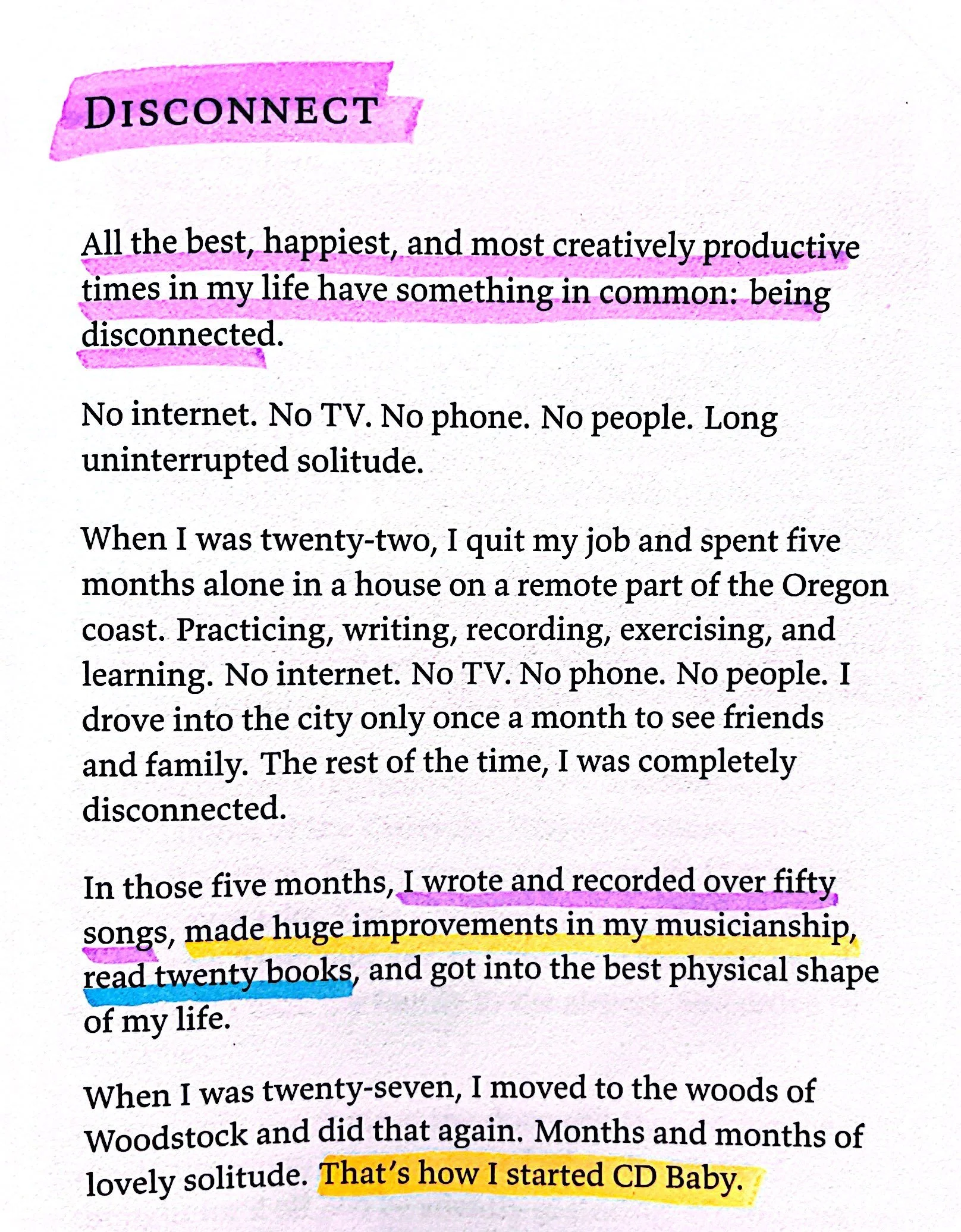

How can disconnecting improve our productivity?

This is a theme that I see repeatedly just about every productivity or wellness book that I’ve read. In my opinion, the best outputs in life come from a interchanging periods of intense connection with intense disconnection.

I’ve found that scheduling regular times to disconnect (say at least once or twice per week) has had a big impact on both my creative output as well as my happiness.

Naturally, highly motivated and goal-oriented students are great at putting their head down, working hard, and continuing to move forward even when times get challenging. In my opinion, medical students are great at this. They have years of proving themselves by studying hard and aiming at the goal of becoming a physician. And this is great.

However, now as a resident, I found it helpful to occasionally take a step back and look at the direction that my momentum is going. What things in life are most valuable to me? What people, environments, and activities energize me the most? What skills do I have that I can leverage to contribute more to those around me?

I’ve found that the answers to these questions become most clear to me when I take a minute to disconnect.

What are my favorite ways to disconnect?

Going for a walk outside without my phone (or with just my airpods to listen to relaxing music)

Laying in the sun on my balcony with my headphones in

Doing a short meditation on the “Headspace” app

These activities let all of the underlying thoughts and feelings bubble to the surface of my mind.

The short periods of disconnection usually provide me with the best ideas and the best answers to these questions.

How might “I don’t know” be the smartest answer?

I think about this concept a lot as it relates to communication between providers in the medical community. Frequently I will hear Specialist A harp on Specialist B for something that they believe wasn’t completed optimally.

I’ve observed physicians do this in every specialty, including Emergency Medicine. I think at the end of the day, every specialty has different training then others, and therefore different experiences, therefore different opinions on how certain cases should be handled.

Of course Specialist A has a different opinion than Specialist B. They have different training.

This is how I think this relates to Emergency Medicine:

Any resident (or anybody in a teaching position) that adopts this mindset has potential to make a big impact on both their learning, and the learning of those they are teaching.

Medical students ask great questions. Although there are many questions residents know the answers to, there are occasions when a great question is asked and we simply don’t know the answer.

For many residents, this is an incredibly fearful situation to be in. Commonly, resident physicians feel a lot of pressure to know all the answers.

One day at hit me - How dumb is it to feel this pressure? It doesn’t make any sense.

Certainly, I have years of training ahead of most medical students. Therefore, I will be fairly confident in many questions they ask. However, when I ask a question that I don’t know, this is actually better than an answer. It provides an opportunity for me to learn, and feels in the holes of my knowledge with an emergency medicine.

Instead, when we don’t know something, an alternative response could be:

“That’s a great question. I don’t know the answer to that one. Let’s look it up and figure it out together.”

This gives an opportunity for me, my students, and everyone in the group to learn.

I think this shows that everyone is human, and fosters a mindset of lifelong learning, and builds camaraderie within the team.

How can the mindset of “Everything is my responsibility” help us grow?

I found this one in particular to be very helpful.

Whenever something doesn’t go the way I hoped it would an emergency department, I think to myself, “Dang it. I should have communicated that better.”

It’s not even helpful to think this but also communicate it to whoever I’m working with. Rather than having others feel guilty about a mistake, they feel empowered to improve to avoid it happening again.

It’s also helps give me peace of mind, and the feeling that many things can be within my control if I can communicate well.

Why is “unlearning” important for learning?

This one is interesting to think about how the practice of medicine evolved as a whole.

As a medical student and resident, it can be common to hear the answer “Because that’s how we’ve always done it” as a response when asked why a protocol/process is a certain way.

Of course, if research and evidence supports a certain practice, then we have a lot of reason to continue practices the way they are. If not, then I think the concepts on this page is really interesting. It makes me think about what things might have the potential to be improved if physicians adopted more of this mindset in more situations.

Taking career advice: Listen to the melody, listen to the counter-melody, and then form your own opinion.

This is another page that motivated me to create this website. I enjoy sharing thoughts and ideas, and certainly everything on this website is just one melody. There are mini countermelody‘s out in the world that go against many of these ideas, and that’s great. They keep us all thinking.

There’s a strong chance that many of the concepts on this website might not be helpful.

I think with most important is to keep a learning mindset, learn from a broad area of references, and take parts and pieces what resonates with us to improve our practice as physicians.